hello@breathestrong.com

hello@breathestrong.com

Home > Exercises

Functional Breathing Training Exercises

When we think of the trunk musculature in a sporting context we most likely think about its

role in core stabilisation, or even in postural control; we might even think about how trunk

muscles contribute to movements such as swinging a racquet. However, most people will not

consider how these roles interact with one another, or more importantly, how they interact

with breathing. Virtually all sports involve movements that implicitly perturb posture (football),

require trunk stabilisation (rugby), incorporate trunk rotation (tennis), and/or compress the

trunk (rowing), whilst simultaneously increasing the demand for breathing. Breathing is brought

about by a complex group of trunk muscles that include the diaphragm, rib cage muscles and abdominal

muscles. These are the same muscles that are responsible for trunk stabilisation, postural control and/or movement.

The diaphragm is one of the best known, but most underestimated trunk muscle. Whilst its role in

breathing is obvious, its roles in postural stabilisation and control are not. For example, the

diaphragm is an important contributor to the increase in intra-abdominal pressure that stiffens

the trunk and stabilises the spine. It also works in synergy with transversus abdominis (TA) to

preserve postural control (prevent falling). These vital roles are illustrated by the fact that

both TA and diaphragm contract automatically in anticipation of actions that destabilise and/or

load the trunk. These contractions occur irrespective of the phase of breathing, but when ‘push

comes to shove’, the diaphragm’s role in breathing always takes precedence over its

non-respiratory roles. So in situations of high breathing demand, such as exercise, the non-respiratory

roles of the diaphragm are compromised, which may lead to an increased risk of injury and/or an increased

risk of falling or loss of balance.

Interestingly, when the inspiratory muscles (including the diaphragm) are fatigued specifically,

people adopt less efficient postural control strategies than in the un-fatigued state, which

supports the notion that breathing muscles play a vital role in balance. It’s also been

shown that if the inspiratory muscles are fatigued prior to an isometic trunk extension test,

fatigue of the back muscles occurs more quickly. This suggests that inhibiting the contribution

of the inspiratory muscles to trunk extension places greater demands upon the back musculature.

These data highlight the vital, but hitherto unseen, role played by the inspiratory muscles

in postural control and core stability.

The complex, often conflicting, demands placed upon the trunk musculature during sport have important

implications for any sport where breathing demands is high. Furthermore, recognition of these

conflicts requires a re-evaluation of how the trunk muscles are trained to accommodate conflicting

roles. Virtually the only contexts in which breathing is trained as part of a functional training

activity are yoga, Pilates and the martial arts. Given what is known about the non-respiratory

roles of the breathing muscles, the failure of modern sports to do likewise seems like an oversight.

Functional breathing training is a response to an important development that has taken place in

rehabilitation and conditioning over recent years—the realisation that training using functional

movement patterns is more effective and safer. However, the missing link in the current practice

of functional training is the integration of breathing, and the recognition that breathing muscles

make a fundamental contribution to movement. The Breathe Strong techniques I have developed bridge

this gap, and will help you to achieve the best results from your breathing and functional training.

Functional breathing training not only enhances performance, it also reduces the risk of injury,

because it enables the breathing muscles to accommodate their role in helping to stabilise the body’s

core more effectively.

Sample exercises from ‘Breathe Strong, Perform Better’

Below I have provided a few examples of functional breathing exercises. The first section contains a selection of ‘generic’ lumbo-pelvic stabilising exercises that are relevant to virtually all sports. The second section contains some examples of sport-specific exercises. An extensive library of sport-specific exercises can be found in ‘Breathe Strong, Perform Better’. The book also provides readers with step by step instructions and the insights required to develop their own functional breathing training exercises.

Lumbo-pelvic stabilising exercises

This section contains some examples of generic lumbo-pelvic stabilising exercises that can be enhanced

by the addition of a breathing challenge. The temptation during these activities is to deal with the

conflict between breathing and the demands of the exercise by holding one’s breath - resist this temptation!

During static exercises such as the plank, breathing should be deep, forceful and rhythmic (~10 to 15 breaths per minute)

for the duration of the ‘hold’. During exercises that involve movements, inhalation and exhalation should

coincide with movement, but the phase should be switched within or between sets so that both directions of

movements and both breathing phases coincide during the exercise. For example, in the case of

the ‘T Push-up’, start in the push-up position with elbows extended feet together and hands

shoulder width apart, then lower the trunk and exhale. Next, push back up, lift the right arm up

and rotate the body until it forms a T shape; deep, forceful inhalation should coincide with the arm

lift and the body rotation. Hold briefly and exhale before returning to the push-up start

position with elbows extended, then inhale again. Repeat the movements, this time lifting the left arm.

The inhalation and exhalation phases should be swapped between sets.

Plank and ‘mountain climber’ plank

Bridge with knees bent

T push-up

Barbell overhead step up

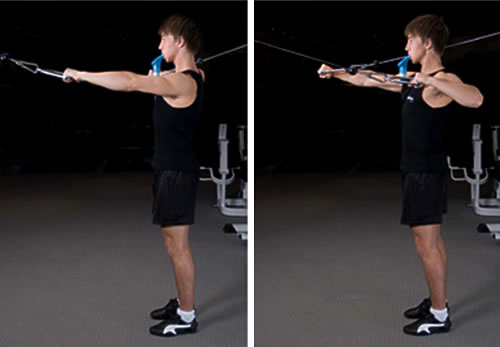

Cable push-Pull

Sport-specific exercise examples

Below are a handful of sport-specific functional breathing training exercises that target situations in which breathing and movement may come into conflict during sports. Further information on how to develop your own exercises can be found in ‘Breathe Strong, Perform Better’.

Running: Dumbbell running

This exercise creates a postural destabilising force. Arm movements should be rapid, but breathing should remain

deep, forceful and rhythmic (~10 to 15 breaths per minute).

Rowing: Swiss ball hip extension

This exercise simulates the postural challenge created at the finish, which is one of the

two most common positions for most rowers to inhale (the second being the catch).

Cycling and rowing: Ab Crush

This exercise restricts movement of the abdominal wall and simulates the mechanical

impedance created during cycling in ‘aerobars’ and at the catch of the rowing stroke.

Swimming: Swiss ball hyperextension

This exercise simulates the challenge created during the breathing phase of breaststroke.

In this case, inhalation always coincides with trunk extension, since this is the

only position in which breathing takes place during the stroke.

Basketball: Single leg hip/shoulder lift

This exercise simulates the challenge posed by lifting and reaching overhead.

Racquet sports: Rotating chest press

This exercise addresses the trunk rotators, which make an important contribution to developing racquet speed.

Skiing: Balance squat

This exercise ensures that breathing does not jeopardise postural control during squatting and extending movements.

Find out more about functional breathing training in ‘Breathe Strong, Perform Better’.

Sign up for updates

Sign up for occasional e-mail updates from Prof Alison McConnell about Breathe Strong and get instant access to bonus material from "Breathe Strong Perform Better".

Find out more >

Breathe Strong Training

Breathe Strong training is the quickest and easiest way to improve your performance and enhance your enjoyment of sport.

Find out more >

"Breathe Strong Perform Better"

Based on academic research spanning two decades, this book explains how anyone can benefit from breathing training the Breathe Strong way.

Find out more >